This week, England’s government announced that it would introduce a new policy to ban student cell-phone use in public schools.

Citing the dangers of bullying and distractions, Education Secretary Gillian Keegan said that students would not even be permitted to check their screens during breaks. “Today, one of the biggest issues facing children and teachers is grappling with the impact of smartphones in our schools,” she stated.

While Americans may instinctively recoil at such draconian measures, the effort shouldn’t be dismissed out-of-hand. As social psychologist Jonathan Haidt has meticulously detailed, the data suggesting a dramatic spike in mental health crises among the “iGen” — a term coined by Dr. Jean Twenge to describe those raised in the age of the smartphone — is now well-documented.

The question remains, however: what does this accomplish? As politicians hope to keep children from spending too much time on TikTok, Mark Zuckerberg is busy giving the first interview in the Metaverse. Barbarians at the gate? If anything, they are already charging their VR headset in your living room.

The disconnect epitomizes a world hurtling into a new age, in which the idea of “technology as tool” is becoming rapidly deconstructed. Part of the chaos seems due to the fact that such a definition is stuck in an infinite teleological feedback loop — “technology, a tool for what?”

Thus, the pendulum of to-be-determined technological value constantly oscillates between an idolizing and a demonizing. It is striking that in a modern world premised on limitless possibilities, there seems to be only two options when it comes to thinking about technology’s role: either the technocratic blissful optimism of “progress,” or a postmodern despair which regards man, if left to his own devices, as governed by machine.

This phenomenon is not new. In his radio broadcast for Christmas 1953, Pope Pius XII identified the two ideological camps and tried to chart a path between them.

Starting from the teleological affirmation that “technical progress comes from God and therefore can and must lead to God,” the pope attempted to break the dichotomy by refusing to cast technology as value-neutral. But at the same time, he warned that without this ordering towards God, a “technical spirit” would assume its place and cause “grave spiritual danger” by trying to immanentize the eschaton:

Today it is seen with increasing clarity that its undue exaltation has blinded the eyes of modern men, has made their ears deaf, so much so that what the Book of Wisdom scourged in the idolaters of its time (13:1) comes true in them; they are incapable of understanding from the visible world the One who is, of discovering the worker from his work; and even more today, for those who walk in darkness, the world of the supernatural and the work of Redemption, which transcends all nature and was accomplished by Jesus Christ, remain shrouded in total obscurity.

Pius did not fall for the postmodern pessimism of his contemporaries, rather he applauded the “splendor and performance” of technological advancement, in that it harnesses the forces of nature and “enables a mode of production, which replaces and magnifies human labor energy.” Done with the right intention, “it is clear that every search and discovery of the forces of nature, carried out by technique, results in search and discovery of the greatness, wisdom, and harmony of God.”

But he was also careful to avoid the Icarian naïveté of those who assumed that technological progress could only be cast as a positive. Pius concluded his address by warning that “the danger is so great that, from the cradle of the eternal Prince of Peace We have had to utter grave words, even at the risk of provoking even greater fears.” In the context of two world wars, millions dead, and the looming threat of the Cold War, it is clear why he would be worried about what this spirit could usher in.

Nearly 70 years later, however, it seems that not only has the technical spirit triumphed, but also that the stakes have been lowered — on both sides. There’s neither nuclear armageddon nor utopia. Instead, what’s left is a resounding “meh.” As Peter Thiel famously quipped, “we wanted flying cars; instead we got 140 characters.”

So what really animates this “technical spirit?”

***

For Evelyn Waugh, the answer was clear.

In a review of J.F. Powers’s Prince of Darkness and Other Stories (1947), Waugh, a Catholic convert, commented that the work was “a magnificent study of sloth — a sin which has not attracted much attention of late and which, perhaps, is the besetting sin of the age. Catholic novelists have dealt at length with lust, blasphemy, cruelty and greed — these provide obvious dramatic possibilities. We have been inclined to wink at sloth; even, in a world of go-getters, almost to praise it.”

It is interesting to compare Waugh’s opinion with that of Evagrius of Pontus (d. 399), the Desert Father who is credited with having first enumerated the eight logismoi or “wicked thoughts” which eventually became the deadly list of seven that we hold today. For while Evagrius did not discount gluttony, lust, avarice, wrath, sadness, and vainglory or pride, he saw that “the demon of acedia, also called the noonday demon, is the one that causes the most serious trouble of all.”

That a fourth-century monk and a 20th-century writer would agree on the dangers of the “noonday demon” suggests that sloth, acedia, ennui — whatever you may call it — deserves its recognition as a deep-seated problem. But what is it, exactly?

Acedia is derived from the ancient Greek word akēdeia meaning “lack of care.” Referencing St. John Damascene, the Catechism names it as a capital vice — from the Latin caput, meaning “head” — because it “engender[s] other sins” (#1866). Damascene, a contemporary of Evagrius who brought his writings to the Latin West, described it as “a sort of heavy sadness” (quaedam tristitia aggravans) that presses down on a man’s mind in such a way that no activity pleases him (ut nihil ei agere libeat).”

In question 35 of the Secunda Secundae of the Summa Theologiae, St. Thomas Aquinas tackles acedia. He defines it as running contrary to the joy that springs from charity: “to be saddened by the divine good, over which charity rejoices, belongs to a special vice that is called acedia” (ST. II-II, q.35, a.2). An act of the intellectual appetite (the will), acedia “burdens a man in such a way that it draws him back totally from good works” (ST. II-II, q.35, a.1).

Thus, the capital nature of acedia renders itself teleological in scope. As Aquinas explains, a vice is considered capital when it “easily gives rise to others as being their final cause.” (ST. II-II, q.35, a.4).

In this context, Pius’s critique of the “technical spirit” takes on a whole new light:

However, it seems undeniable that technique itself, which has reached the heyday of splendor and performance in our century, is, by circumstance, turning into a grave spiritual danger. It seems to communicate to modern man, prone before its altar, a sense of self-sufficiency and fulfillment of his aspirations for boundless knowledge and power. With its manifold uses, with the absolute confidence it commands, with the inexhaustible possibilities it promises, modern technology deploys around contemporary man a vision so vast as to be confused by many with infinity itself. An impossible autonomy is attributed to it as a consequence, which in turn is transformed in the thinking of some into an erroneous conception of life and the world.

Following in the footsteps of the “Father of Lies,” the noonday demon tempts man with Heaven here on Earth — expressed today in the seemingly limitless possibilities that technology offers. But in the end, technology alone can never satisfy his deepest desires, and such a false promise of infinite freedom leaves him empty-handed. To maintain the con, acedia offers alternating bouts of hyperactivity and lethargy — once again epitomized in the attention economy which dominates modern technology. Ultimately, acedia’s goal is accomplished: overstimulated and stupefied, man’s vocational vision is sadly lowered.

At the end of his work Acedia and Its Discontents: Metaphysical Boredom in an Empire of Desire, R.J. Snell aptly captures the modern repercussions of this ancient vice:

Like all the demonic thoughts, the vice of sloth promises life but brings death; the way of the Cross demands death but gives life. Given our deep acedia, we choose the lie, recoiling in abject disgust and sadness at the truth of being. Thinking we retain vitality by rejecting the Cross, we stumble into enervation, unable to act, impotent. Glancing at our own society, we observe remarkable dynamism in trade, technology, transportation, entertainment — really incredible advances — but find inertia and tiredness in the domain of value. We seem to have no will for life, choosing sterile sex, rejecting (or deforming) marriage, dismembering nascent life in the womb, while endlessly seeking pleasant distractions — anything to keep us from facing honestly the truth of our being and its noble demands. Compared to the youthful effervescence of the saints, desire’s empire seems like a love of death, alternating between crazed attempts to prolong the baubles of our entertainments, whatever the expense or exploitation, or wearily sinking into despair, refusing to propagate our culture or bodies. We know not what we are for, or if we do we shrink from its weighty labor.

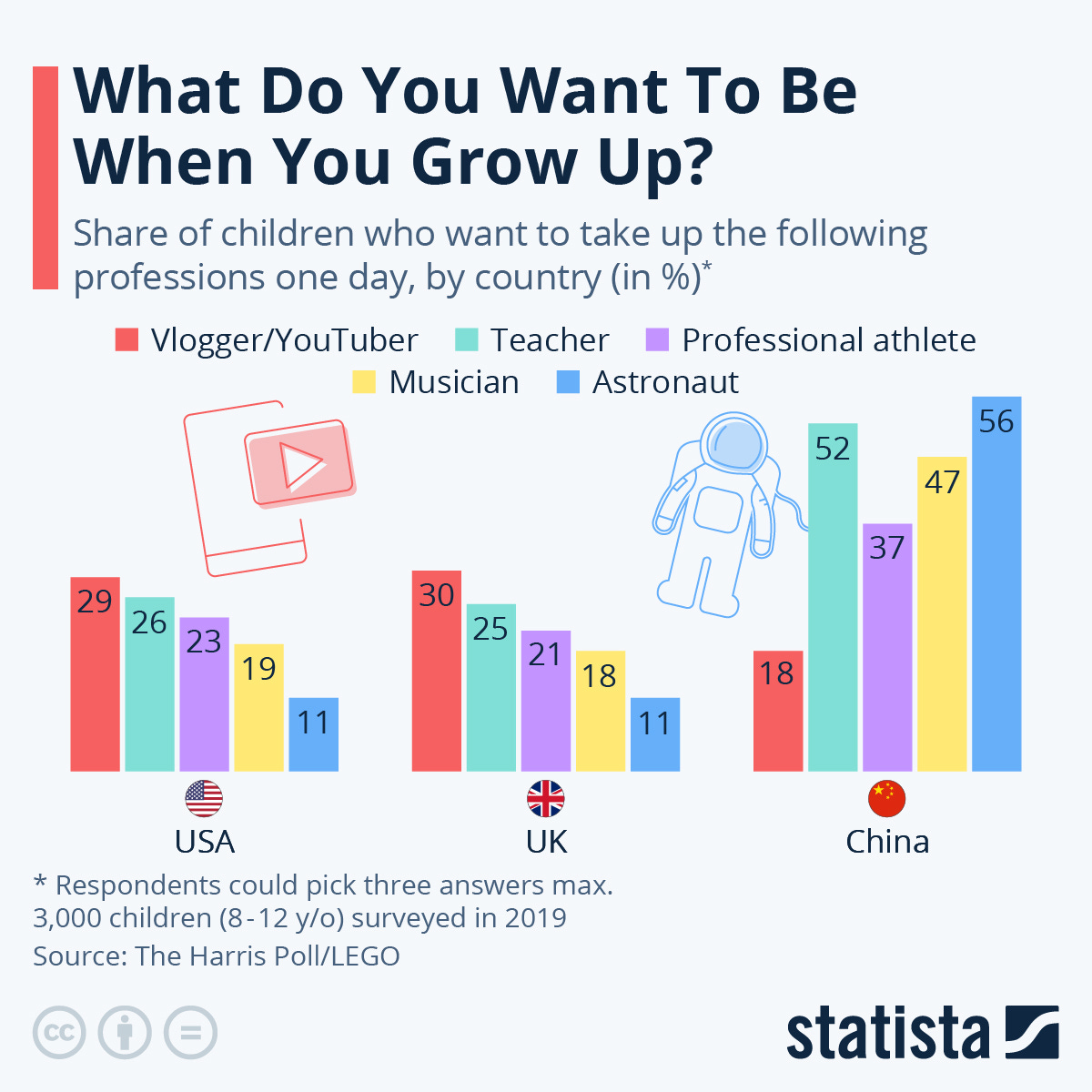

Acedia seeks to carve out man’s teleological orientation in such a way that it renders his meaning listless and his work rudderless. And what better illustration of this phenomenon than the current state of American vocational aspiration? After all, why do U.S. kids prefer being a vlogger/YouTuber to being an astronaut?

***

Snell’s book — the title of which plays on Freud’s foundational work Das Unbehagen in der Kultur — is divided into three parts. Rather than open with a discussion of acedia, it chooses to explain why acedia matters — in that it represents a direct assault on man’s “weighty gift of responsibility.”

Like Pius, Snell wants to defend man’s call from God to work. But he also emphasizes that call as fundamentally relational. Snell uses Genesis 2 to show the interplay between the Hebrew words ish (“man”) and ishsh-ah (“woman); adam (“man”) and adam-ah (“ground”) — arguing that “we are from dirt … we are also for the dirt.”1 Ultimately, made in God’s image and likeness, man is called to see caritas, willing the good of the other, as the foundation of his work in both the objective and the subjective dimensions of creation.

Since God can make things come from nothing merely by willing it so, his will is genuinely productive. But God’s love also acknowledges the goodness of existence even if all exists only by his will. Consider the remarkable fact that God not only creates but sustains the world. Since the existence of everything at every moment depends upon God’s eternal and unchanging will to “Let it be! Esse!,” then all that is, even just now, exists because God affirms that it is good for it to be. Et Deus vidit quod esset bonum. Et factum est ita. And it was so, and God saw that it was good.

The teaching of Genesis 2 moves Adam into a position of loving Eve in this basic way, responding to her presence with recognition and affirmation — “At last!” —seeing Eve as God sees her, as good. God saw that she was good — will Adam? He does, and so they stand before each other in mutual regard, without shame, without fear, and without concupiscence.

Thus, because acedia runs contrary to charity, Snell moves on to describe how it results in an “unbearable weightiness of being” and serves as an explicit rejection of the vision articulated in Genesis. He sees it especially prevalent in an “inordinate love of freedom” — a hallmark of modern society — which leads to a state in which one idolizes subjective experience at the expense of loving objective reality.

Boredom has a history. The term itself did not exist until the eighteenth century and was not used regularly until the nineteenth—the Oxford English Dictionary records a letter by the Earl of Carlisle in 1768 about his friends who are bored by Frenchmen. This boredom was new, “different from the dullness, lassitude and tedium people had no doubt been experiencing for centuries.” Boredom, then, is a phenomenon of modernity, in some sense possible only in the disenchanted world of modernity.

Using the terminology of Martin Heidegger, Snell traces the evolution of “boredom” as a concept that everyone experiences — whether it be “in the face of tedium, we wish for time to be whiled away” (being bored with something) or “time was filled well, you did not wish it to be whiled away, but the party did not satisfy” (boring oneself with something) — to a third, exclusively modern version.

The third form of boredom identified by Heidegger is being bored by boredom itself. In other boredoms one is bored by the emptiness of objects, situations, and activities, but in this third boredom everything leaves one empty, including, and perhaps especially, one’s own self. Bored with everything, there is no hiding place, no ability to lose oneself in any interesting and distracting reality, and one is, says Heidegger, compelled to listen. To what? Listen to what? To the indifference of it all. To the meaninglessness of everything, even the meaninglessness of our own existence.

This is the type of acedia that Waugh recognized amongst his peers, especially because “in a world of go-getters” it is able to shroud its vicious nature. By ignoring the objective value of created reality, acedia incentivizes the techno-optimist vision of value-neutral progress — leading to the criterion of seeing the world as “standing-reserve,” a term coined by Heidegger to epitomize the paradigm shift away from the ontological and towards the instrumental. As Snell explains:

Bearing infinite weight, things possess their own interiority and integrity and so they were understood by the medievals to be subjects rather than mere objects of being. Not so for the moderns, however, who reduced things to mere objects with extension. Flattening and thinning things to matter in space, objects were stripped of their glory … Objects become beautiful if they please us, according to our subjective taste, rather than demanding our delight as a matter of justice; objects become good if they serve us, according to our subjective purposes, rather than demand our willing them in keeping with God’s own judgment and instruction.

Snell calls this phenomenon “the empire of desire” — man’s relation to creation is no longer that of steward, but of consumer. And technology, infused with this spirit, sees reality as ultimately exploitable. Embraced enthusiastically, however, such an approach leads to nothing but nihilism. Rather than face the emptiness of it all, acedia seeks in off-ramp from total self-destruction via constant distraction and dissipation in petty pursuits. Don’t even bother moving — the algorithm will always suggest another dopamine hit.

So what is the solution? “Disenchanted, the world is bereft of loveliness to the slothful — and there are many afflicted by sloth in our own time, an epoch subjected to sloth’s terrible covenant,” Snell acknowledges. But this is no time to abandon ship. In fact, Snell succinctly grasps how both the techno-optimist and techno-pessimist camps fall into the same trap of acedia:

We know that our ultimate vocation is supernatural rather than natural, rendering our natural vocation “penultimate” but still good. Two errors tempt us: the first lowers our vision and considers natural goods ultimate, while the second wishes to cast off this mortal coil as nothing more than a distraction, maybe even evil, turning only to the supernatural good. Both overlook the integration of supernatural and natural vocations.

Rather, he argues that what is called for is a return to the two-part mission of adam in the here-and-now: embracing gift (Eve) and responsibility (Eden).

Since our seeing and willing are damaged by sloth, we require instruction in order to appropriate the fullness of virtue. As God gave two forms of instruction to assist Adam in understanding and welcoming his own subjectivity — the search for a helper and the creation mandates — so we find God’s help for our slothful and bored culture. First, as Adam was to welcome Eve in delight, we recover a healthy approval through the practice of Sabbath, which is not an absence or negation of work but a full presence of festive delight in goodness. Sabbath retrains sight and love, guiding us in entering fullness after the bondage of Egypt (sloth, boredom, and nihilism).

If Sabbath retrains us so that we may, like Adam, respond with a delighted “At last,” so also the “second” set of God’s instructions: the mandates of filling, tending, governing, and keeping the garden. Just as Sabbath resists sloth with a practice of love’s approval, sloth needs to be resisted with the fullness of the mandates, a retraining in good work.

Only in this way can man return to his original call to magnanimity, which cannot coexist with acedia. It is at the end where Snell is most lucid, describing acedia as a “a kind of perverted humility refusing the greatness demanded of the human person.”

Man’s nature, as made in the image and likeness of God, gives him the vision to see the objectively good value of technology, despite its obvious modern challenges. Though algorithmic acedia will always have something new to pique curiosity, the challenge is to recognize the Siren Song for what it is and to face it head-on. As Evagrius advised his fellow monks in the face of acedia, “the time of temptation is not the time to leave one’s cell, devising plausible pretexts. Rather, stand there firmly and be patient.” Snell echoes the sentiment: “If we embrace our place, sloth would be overcome and we would act as we were meant.”

This is the first in a seven-part series on the capital sins. For Part II on gluttony, click here.

Snell, R. J. Acedia and Its Discontents: Metaphysical Boredom in an Empire of Desire. Angelico Press, 2015.

Acedia can be overcome by experiencing the fulfillment of man's desire in Christ. Christianity is not merely a response to reason or a proposal for moral conversion; it is also an answer to man's deepest desires for happiness. This longing can only be satisfied through a life-giving encounter with Christ. The transformation brought about by Christ's life within us is the only response that truly addresses the desires of the human heart.

Aquinas states that sin is always to be shunned, but the assaults of sin should be overcome—sometimes by flight, sometimes by resistance. Flight is necessary when continued thoughts intensify the temptation to sin, as in the case of lust. Resistance is required when persistence in thought weakens the temptation, which arises from some trivial consideration. This is applicable to sloth because the more we contemplate spiritual goods, the more pleasing they become, and sloth promptly diminishes" (S. Th. II-II, q. 35, a. 1, ad 4). This reflection on the spiritual goods received finds expression in prayer, in the habitual attitude of gratitude to God, and in spiritual direction. Everyone can learn to list the talents God has entrusted to them (cf. Mt 25:14-30).

Those suffering from sloth may have everything they need to be happy, but they often fail to recognize it, locking themselves in sadness. The effort of will alone won't suffice unless it transforms into an act of love. Someone grappling with sloth needs to redirect their attention away from self-centeredness and instead focus on God and neighbor. Sloth is a sin against charity and can genuinely be overcome through love. This is where the essence of victory against acedia lies—in love:

a) Understanding the meaning of sorrow opens a door to comprehending even psychological distress. The epistle to the Hebrews advises meditating on Christ's Passion to overcome a feeling similar to acedia: “Consider how he endured such opposition from sinners, in order that you may not grow weary and lose heart.”(Heb. 12:2-3). Meditating on the Passion helps prevent losing heart, especially because the believer discovers how much the Paschal Mystery is to be reproduced in them, even with the offering of their internal discomforts, which are at least partially consequences of their faults.

b) Rediscovering love for and from Christ and the possibility of identifying with Him is crucial. The battle against acedia must primarily be fueled by love for Christ. The key to perseverance lies in practical and active love for Christ: "What is the secret of perseverance? Love. Fall in love, and you will not leave Him" (St. Josemaria, The Way, no. 999). This love for Christ is not only possible but can be renewed at every stage of our lives because it is the same God who comes to love within us. We love with the same power as God loves. "Christ frees us from acedia" because, through the effects of the Incarnation today, He opens us to the joyful hope of identification with Him (cf. St. Thomas, Summa contra Gentiles, lib. IV, c. 54).

Nice piece! I would also notice that early Church Fathers saw acedia what we understand by sloth today - in the sense of lacking motivation to do something - and more like a sadness of thinking spiritual are too hard to be achieved and therefore no worthy of the effort. Something more akin to the lack of hope.

Also in this sense, technology and material progress in general can contribute to this perception that spiritual goods are not worthy of pursuing since we already have a comfortable life as it is.